Research, applied research, knowledge transfer and indicators selected in the U-Multirank project

Research, knowledge transfer and indicators selected in the U-Map project

Ben Jongbloed, Frans Kaiser, Frans van Vught

November 2010

In the U-Map classification, the activities of a higher education institution are captured (‘mapped’) using six dimensions:

1. |

Educational profile |

2. |

Student body |

3. |

Research involvement |

4. |

Knowledge transfer |

5. |

International orientation |

6. |

Regional engagement |

Some commentators perceive the research dimension of U-Map and its underlying indicators as too narrow and overemphasising the traditional scientific method. There is a growing diversity of research missions across the classical research universities and the universities of applied sciences. The feeling is that U-Map is overly reliant on journal publication and citation indicators. Some claim that this does not provide a proper characterization of the knowledge-production and knowledge-dissemination activities of those higher education institutions other than the research universities. Given the increasing complexity of the research function of higher education institutions and the fact that higher education institutions (HEIs) outside the university sector are engaging in research (Kyvik and Lepori, 2010), one would have to adopt a broad definition of research. Such a broad definition needs to incorporate elements of both basic and practice-oriented research.

In this note, the position taken in the U-Map project regarding the research dimension and the knowledge transfer dimension is clarified.

The U-Map position is based on analyses of the relevant research literature, common practice in higher education (policy) debates and the outcomes of intense stakeholder consultations over the past five years. We first address the research dimension and then we extend the discussion to incorporate elements of knowledge transfer.

![]() Views on research activities

Views on research activities

What is research? To what types of activities do we refer to when we talk about research? We distinguish two views on what research is: a broad view and a narrow view.

Broad view

The broad view can be described as follows:

‘Research and experimental development (R&D) comprise creative work undertaken on a systematic basis in order to increase the stock of knowledge, including knowledge of man, culture and society, and the use of this stock of knowledge to devise new applications’

The term R&D covers three activities: basic research, applied research and experimental development. Given the increasing complexity of the research function of higher education institutions and its extension beyond PhD awarding institutions, a broad definition of research is called for. Such a broad definition needs to incorporate elements of both basic and practice-oriented research. This allows one to capture research activity in the face of a growing diversity of research missions across the classical research universities and the vocational HEIs.

A similar broad view is used in the Dublin descriptors

The word ‘research’ is used to cover a wide variety of activities, with the context often related to a field of study; the term is used here to represent a careful study or investigation based on a systematic understanding and critical awareness of knowledge. The word is used in an inclusive way to accommodate the range of activities that support original and innovative work in the whole range of academic, professional and technological fields, including the humanities, and traditional, performing, and other creative arts. It is not used in any limited or restricted sense, or relating solely to a traditional 'scientific method'.

Narrow view

The ‘narrow’ view on research separates the research activities focused on research communications within the higher education and research community from the research activities focused at the wider world. In this view the former is considered to be research whereas the latter type of activities is seen as knowledge transfer activities.

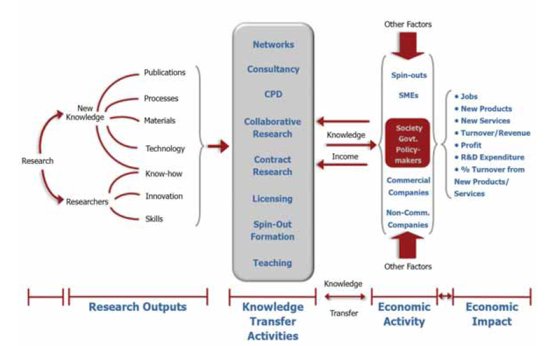

This is illustrated in figure 1, where research is to be understood as the left hand side. Research produces new knowledge, partly codified in publications and technology and partly embodied in people that have know how and skills that can be applied in other contexts. These contexts are located in the right hand side. Knowledge transfer activity is located in the middle of the diagram.

Figure 1: Model of Knowledge Transfer within the Innovation Ecosystem

Source: Holi (2008)

Source: Holi (2008)

Knowledge transfer refers broadly to the transfer of knowledge, expertise and intellectually linked assets to economy, society and culture. The knowledge transfer function has become increasingly relevant for higher education institutions as many nations and regions strive to make more of their science output readily available for cultural, social and economic development. There are large differences between efforts of individual institutions in this respect, partly because of the official mandate of a HEI and partly because of the strategic profile chosen by individual HEIs.

Knowledge transfer is defined as:

the process by which the knowledge, expertise and intellectually linked assets of Higher Education Institutions are constructively applied beyond Higher Education for the wider benefit of the economy and society, through two-way engagement with business, the public sector, cultural and community partners. (Holi et al., 2008).

In the figure, research is separated from knowledge transfer. However, it will immediately be clear that some of the knowledge transfer activities, such as collaborative research and contract research, might just as well be included in the research activity on the left handside of the picture.

![]() Capturing research activities

Capturing research activities

There are many ways to map research activity. One of them is to use the four channels of interaction distinguished by Callon (1992), that is: text, money, people and artefacts.

· |

The text channel is the best known and most referred to in indicators on research activity. Publishing through scientific or popular media is an important research output. |

· |

The money channel refers to the financial contributions that stakeholders pay for research activities. Research grants and contracts with public authorities and external partners are potential indicators. Other R&D-related money flows are generated in activities that situated on the right hand side of figure 2 and are part of knowledge transfer activities. |

· |

People. People carry with them tacit knowledge. To capture research, the number of research staff or doctoral students is a crucial indicator. |

· |

Artefacts. Artefacts are concrete, physical forms in which knowledge can be carried and transferred (such as machinery, software, a musical composition, works of creative art, new materials or modified organisms, technology). |

Important work was done by the Expert Group on Assessment of University-Based Research, delivered to the European Commission’s DG Research. The Expert Group defines research output as referring to the individual journal articles, conference publications, book chapters, artistic performances, films, etc. While journals are the primary publication channel for almost all disciplines, their importance differs across research disciplines. In some fields, books (monographs) play a major role, while book chapters or conference proceedings have a higher status in other fields (see table 1).

Publications are the single most important research outlet of HEIs. However, the complexity of knowledge has led to a diverse range of output formats. The following is a list of research-based outputs: academic texts, audio visual recordings, computer software and databases, technical drawings, designs or working models, major theatrical works, art exhibitions, patents or plant breeding rights, policy documents or briefs, research or technical reports, legal cases, maps, translations or editing of major works.

Table 1 identifies the primary form of communications for the main discipline groups. For example, while natural and life scientists write books, their primary outlet is peer-reviewed journal articles. Engineering scientists primarily publish in conference proceedings although they also publish in journals and design prototypes. Social scientists and humanists have a wide range of outputs of which books are important sources of communication, while the arts produce major art works, compositions and media productions. In summary, Table 1 illustrates the diversity of research outlets, and why the focus only on journal articles cannot do justice to the contribution that other disciplines make.

Table 1: Primary form of written communications by discipline group

Natural sciences |

Life sciences |

Engineering sciences |

Social sciences & Humanities |

Arts |

|

Journal article |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Conference proceedings |

X |

||||

Book chapters |

X |

||||

Monographs/Books |

X |

||||

Artefacts |

X |

||||

Prototypes |

X |

Source: Expert Group on Assessment of University-Based Research (2010)

It should be stressed that not all texts, written communications etcetera are peer-reviewed. They also include professional and popular publications aimed at a professional audience or the public in general. Some of these texts and outputs are published in journals, books, or other media that do not exercise a form of peer-review, as they are aimed at a laymen’s audience. In the U-Map datacollection, next to the peer-reviewed academic publications, we include professional publications and peer-reviewed other research products. One may argue that the latter two categories, however, are more like knowledge transfer activities. There are more or less outputs that are ‘ready for use’ and can be carried and transferred more or less immediately to users.

A typical classification of mechanisms and channels for knowledge transfer between HEIs and other actors is listed in the table below (Holi et al., 2008), along with a number of indicators to assess the quantity of the different facets of knowledge transfer. Along these channels, HEIs develop relations with a variety of potential ‘users’: entrepreneurs, consumers, policy makers, regional actors, etc.

Table 2: Knowledge Transfer Mechanisms and indicators

|

Mechanism of knowledge transfer |

Measures of quantity |

Networks |

# of people met at events which led to other knowledge transfer activities |

Continuing Professional Development (CPD) |

Income from courses. # of courses held, # people and companies that attend |

Consultancy |

# and value/income of contracts, % income relative to total research income, market share, # of client companies, length of client relationship |

Collaborative Research |

# and value/income of contracts, market share, % income relative to total research income, length of client relationship |

Contract research |

# and value/income of contracts, market share, % income relative to total research income, length of client relationship |

Licensing |

# of licenses, income generated from licenses, # of products that arose from licenses |

Spin-outs |

# of spin-outs formed, revenues generated, external investment raised, market value at exit (IPO or trade sale), Physical migration of students to industry |

Teaching |

Graduation rate of students, rate at which students get hired (in industry) |

Publishing |

Publications as a measure of research output |

Source: Based on Holi et al. (2008)

![]() Indicators

Indicators

Looking at the indicators for capturing research activity and performance, we can make the following distinction:

· |

Input indicators measure resources, human, physical and financial, devoted to research. Typical examples are the number of (academic) staff employed or revenues such as competitive, project funding for research. |

· |

Output indicators measure the quantity of research products. Typical examples are the number of papers published or the number of PhDs delivered. |

· |

Outcome relates to a level of performance, or achievement, for instance the contribution research makes to the advancement of scientific scholarly knowledge. |

· |

Impact and benefits refers to the contribution of research outcomes for society, culture, the environment and/or the economy. |

These indicators reflect a wide range of research activity, outputs and outlets across the full spectrum, from discovery to knowledge transfer to innovation.

The measurement of research activity still focuses heavily on traditional measurements of research inputs and outputs: numbers of research staff or doctoral students, research income, awards, and bibliometric data (publications, citations).

Universities and colleges are known for generating new ideas and spurring innovation, and for moving advances in knowledge and technology into the private (business) sector where they can be put to work for the public good. These endeavors collectively are referred to as “technology transfer.” As shown in table 2, the transition of knowledge into practice takes place through a variety of mechanisms, including but not limited to:

1. |

movement of highly skilled students (with technical and business skills) from training to private and public employment; |

2. |

publication of research results in the open academic literature that is read by scientists and engineers in all sectors; |

3. |

personal interaction between generators and users of new knowledge (e.g., through professional meetings, conferences, seminars, industrial liaison programs, and other venues); |

4. |

firm-sponsored (contract) research projects involving firm-institution agreements; |

5. |

multi-firm arrangements such as university-industry cooperative research centers; |

6. |

personal individual faculty and student consulting arrangements with individual private firms; |

7. |

entrepreneurial activity of faculty and students occurring outside of the university without involving university-owned IP; and |

8. |

licensing of IP to established firms or to new start-ups companies. |

Of the eight mechanisms of technology transfer listed above, the first seven offer significant contributions to the economy, yet it is the eighth (licensing of IP ) that is more often discussed, measured, quantified, and debated than the other mechanisms combined. There are several reasons for this. First, patenting and licensing activities by universities are easier to observe and measure than most of the other mechanisms, for example, movement of students and consulting arrangements. Second, in contrast with scholarly publications and most professional interactions, patenting and licensing activities are characterized by readily apparent economic value or distinct potential revenue streams for businesses, universities, and faculty inventors. Third, there has been a dramatic upsurge in patenting and licensing since 1980 – in particular in the life sciences and engineering, and the economic value of licensing is readily apparent.

Yet, when looking at the economic and technological impact of HEIs, many studies and indicators tend to focus on the ‘top of the iceberg’ – on patents, licensing income and scientific papers as manifestations of knowledge exchange between academia and society. The ‘iceberg model’, presented by the OECD and pictured below, can be used to illustrate the fact that there is a lot of interaction going on beyond the quantifiable manifestations in the shape of spin-off companies, licensing income, patents, research contracts, and research publications. Interaction between HEIs and society/business is more than co-publications and spin-offs. In other words, and looking at some of the less-quantifiable and informal channels of knowledge transfer represented also in the bottom part of the iceberg model, there is a great need for a broader model of knowledge transfer backed up by statistics and indicators.

Figure 2: The Iceberg model (OECD, 2002)

![]() Knowledge transfer and research: U-Map position and indicators

Knowledge transfer and research: U-Map position and indicators

We now shall present the position taken in the U-Map project regarding mapping knowledge transfer and research involvement and discuss the indicators selected for inclusion in U-Map, along with their potential shortcomings.

· |

In U-Map research activities are separated from knowledge transfer activities |

In the light of the preceding discussion it is clear that research and knowledge transfer activities are partially overlapping. Despite this, we decided to include two separate dimensions in the U-Map activity profiles: research and knowledge transfer. For a number of reasons.

A separation is in line with the current practice to distinguish between the ‘three missions’ – teaching, research, services to society – of knowledge institutions.

A separation between the research mission and the knowledge transfer mission (or the third mission of HEIs – see Laredo, 2007) is also in line with traditional thinking on the distinction between research activities and innovation.

Distinguishing research and knowledge transfer activities also serves another cause. From the stakeholder consultations we held during the U-Map project we learned that a distinction will provide higher education institutions with the opportunity to become more clearly visible on the knowledge transfer dimension. Integrating research and knowledge transfer into one dimension runs the risk of leading to confounded constructs that mask the true activity profile of a higher education institution.

Summing up, we therefore believe that our choice for two separate dimensions will increase the face validity of the U-Map profile, its acceptance by stakeholders, and the use that will be made of the profile.

· |

In U-Map all channels of communication regarding research and knowledge transfer activities are addressed in the choice of indicators |

The construction of quantitative indicators so far has led to indicators that can at best capture only part of the picture, and is biased towards indicators that address the licensing of intellectual property (IP) from universities to established firms or to new start-up companies. While we will have to make use of such indicators in U-Map we have tried to expand and extend our choice of indicators in order to capture more of the research and knowledge transfer activities of the various types of higher education institutions. This wider scope is expressed through indicators that not just focus on publications or IP-related issues, but that also include monetary indicators, art-related research activities and indicators addressing human resources. The four channels of research communication and the relevant U-Map indicators are:

Text: publications (academic and professional)

Money: expenditure on research; income from knowledge transfer; patent applications, start-ups

People: doctorate production

Artefacts: concerts and exhibitions (other research related outputs)

· |

Responsiveness and flexibility are important characteristics of U-Map |

The U-Map team is aware of the problems, flaws and fallacies of the list of indicators chosen. U-Map welcomes suggestions regarding the refinement of the existing list of indicators and adding or replacing U-Map indicators.

Clarifications of definitions will be implemented whenever needed through updates of the U-Map glossary and the frequently asked questions section on the U-Map website.

A revision of the list of indicators (adding new indicators and/or replacing old indicators) will be discussed and implemented after the start-up phase of U-Map. The revised U-Map tools (version 2.0) will be consistent with the current version of U-Map.

References

Callon, M., Larédo, P., Mustar, P., Birac, A.-M. et Fourest, B. (1992), Defining the Strategic Profile of Research Labs: the Research Compass Card Method, in: Raan, A. F. J. v., (ed.), Science and Technology in a Policy Context, Leiden: DSWO Press.

Expert Group on Assessment of University-Based Research (2010) Assessing Europe’s University-Based Research, European Commission, Brussels

Holi M.T., Wickramasinghe, R. and van Leeuwen, M. (2008), Metrics for the evaluation of knowledge transfer activities at universities. Cambridge: Library House.

Joint Quality Initiative (2004) Shared Dublin descriptors for Short Cycle, First Cycle, Second Cycle and Third Cycle Awards, A report from a Joint Quality Initiative informal group, Dublin

Kyvik, S. and B. Lepori (eds.) (2010), The research mission of higher education institutions outside the university sector, Springer, Dordrecht

OECD (2002), Frascati Manual, proposed standard practice for surveys on research and experimental development, Paris,

OECD (2002) Benchmarking industry-science relationships, Paris

![]() U-Map Indicators

U-Map Indicators

Having described the dimensions of Knowledge Transfer (KT), respectively Research, we conclude with the choice of indicators for these two dimensions in the U-Map project:

Research involvement in U-Map is measured by means of the following pieces of information:

1. |

Peer reviewed publications per fte academic staff. A count of peer reviewed publications of the institution. This includes PhD dissertations and books. Peer review (also known as refereeing) is a process of subjecting an author's scholarly work, research, or ideas to the scrutiny of others who are experts in the same field, before a paper describing this work is published in a journal, book or conference proceedings. |

2. |

A count of all publications published in journals/books/proceedings that are addressed to a professional audience and that can be traced bibliographically, per fte academic staff These publications are not peer reviewed as in the category academic publications. |

3. |

Doctorate degrees awarded per fte academic staff |

4. |

The total amount of financial resources spent on research activities, including expenditure on R&D at academic hospitals and including expenditure on services indirectly related to research (e.g. management and organisation of research, administration, capital expenditure), but excluding the academic hospitals’ expenditure on patient care and other non-research-related general expenditure, as a percentage of total expenditure. |

In the U-MAP project, four indicators were selected to capture Knowledge Transfer:

1. |

The number of new patent applications filed by the institution (or one of its researchers/departments) with a patent office, per fte academic staff |

2. |

The number of research outputs, other than peer-reviewed publications and professional publications, per fte academic staff. These outputs may be found through bibliographical searches and have been documented officially. This category includes exhibition catalogues, musical compositions, designs, and other artefacts that underwent a process of peer review. |

3. |

The average annual number of start-up firms established over the previous three year period by the HEI, per fte academic staff |

4. |

Income from knowledge exchange activities (includes: Income from licensing agreements; Income from copyrighted products; Income from privately funded research contracts) as a percentage of total income. |